|

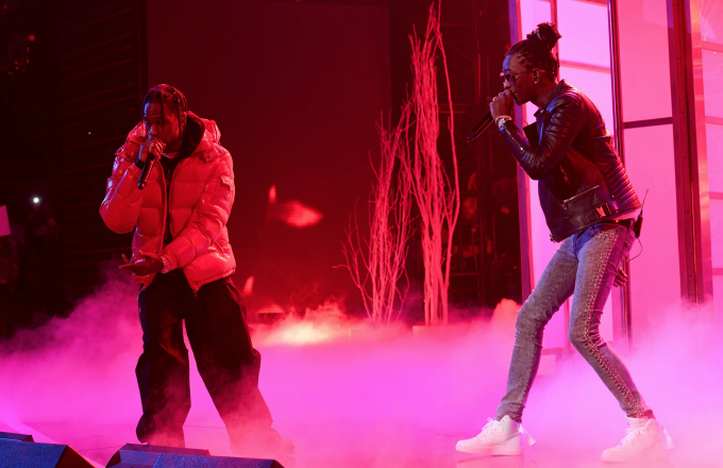

21 Savage has always had his own lane within trap. His uniquely deep and deadpan timbre and his subject matter comprised of criminal anecdotes and murder ballads make him into something resembling a Shakespearean lawbreaker. Tapes like The Slaughter Tape and Savage Mode flaunt an almost theatrical ghetto-centricity, music injected with the desire to present human existence at its most fetishibly and fantastically bleak. It’s the white evangelical’s idea of what inner city gangster music sounds like, a negative stereotype exultantly taken to the hilt. Yet I’ve always found 21’s solo music boring precisely because of this one-note caricature of darkness. For sure, he’s a creative lyricist and he has a real knack for enunciating words catchily. But after a while his style tends to devolve into a depthless drone. In contrast to the psychedelic elements incorporated by melodic trappers like Travis Scott and Playboi Carti, 21’s instrumentals are diminutive in their scope, refusing to adventure beyond the spartan template of 808, snare, kick, hat, etc. There’s no interesting play going on with reverb, sound effects, or vocalisations. His most enjoyable tracks have been carried by excellent production, and specifically that of Metro Boomin, a long-time collaborator, whose mosaics of sound effects and sample-manipulating skills always liven things up. While 21 Savage is more famous now than ever, his new album serves as a litmus test: can he make something by himself that’s stylistically mature, a world of his very own? I Am Greater Than I Was (stylized i am > i was) presents itself as 21 Savage’s duality realized, showing that the cold-hearted killer does in fact have a soft side. But besides the inclusion of some gentler, mellowed beats, which serve 21’s style in no way whatsoever, there’s nothing really indicative of emotional or stylistic maturation. Even 21’s brazenly titled “letter 2 my momma” (which one thinks would be the perfect opportunity to display maturity) sees him ad-libbing “skraight up” after would-be-sincere lines like “I'm still your baby even though I got a child, too.” If you take it sardonically (in that despite his age and fatherhood he still needs his mom’s advice, and the childish ab-libs is tongue in cheek) then it’s sort of funny, but I doubt that’s what he was intending. He botches his own attempt at conveying profundity. In this new album, 21’s aesthetic is split, stretched thin between his trademark style and the more conscious, meaningful side that feels all too forced now. Everything about the album is bizarre. After his song “Don’t Come Out The House” on Metro Boomin’s recent album was lauded for its inclusion of “whisper rapping” -- to my ears more unpleasant than innovative, like inventing a word that no one’s ever going to use -- 21 decided to make a full song dedicated to whispering, titled “asmr.” It has one of the better beats on the album, courtesy of Metro Boomin, but once again the whispering makes the song extremely unplayable. A whispering section would actually be interesting if built around the right ambient beat, but Metro’s drums don’t simmer at all, creating a sour juxtaposition. It’s even more unpleasant simply because 21 doesn’t have a fit-for-whispering inflection, his raspy croak sounding like an annoying friend trying to keep quiet in a library. Other strange lowlights include his descent into sing-songy, AutoTune-lathered decrepitude on “all my friends,” and the most irritating, distracting hi-hat rolls I’ve ever heard on “ball w/o you,” which sounds like someone desperately trying to squirt ketchup out of a bottle with barely anything left over and over again. Perhaps the weirdest thing about the album is that 21 Savage released a second one, a deluxe version, only three days later. The sole discernible difference between the two is that 21 added “out for the night - part 2,” a track that literally copied and pastes the original “out for the night” and adds a less than two minute section featuring an entirely different beat and an entirely different vocalist, Travis Scott. If it wasn’t bolted onto the first bit, you’d have no way of knowing that it was even supposed to be the same track. The appendaged bit is actually great, with massive synthesizers that scan across the soundscape like stadium lights. Travis is ushered in like a holographic superhuman, his verse hitting like an omniscient force along with ad-libs that iterate and reverberate in myriad directions like shapeshifting gusts. It’s an incredibly exuberant performance that’s more deserving of being a single than an accessory to 21’s miserable original cut. What’s most surprising about the album is how unmemorable it is, as I’ve listened to the album quite a few times now and can barely recall a third of the songs. Although the best track by far is “monster,” which has a great beat and feature by Childish Gambino, it’s still only the apex of a hill barely formed. In the past, 21 has usually mustered up at least one track that endured; on Savage Mode, it was “No Heart,” and on Issa Album, it was “Bank Account.” It should be alarming that there’s nothing on here that stands out.

Rating - 1/5

0 Comments

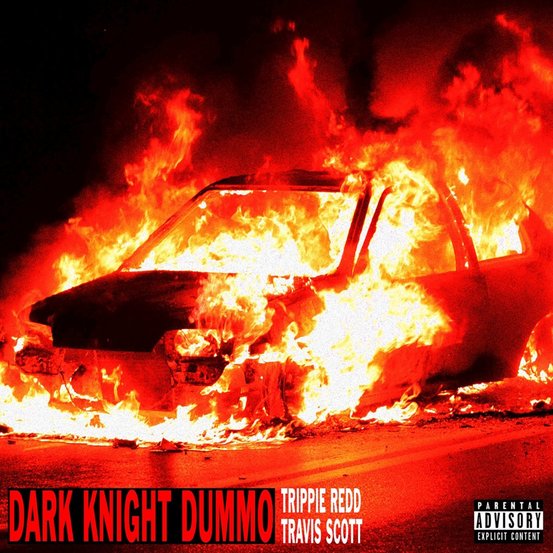

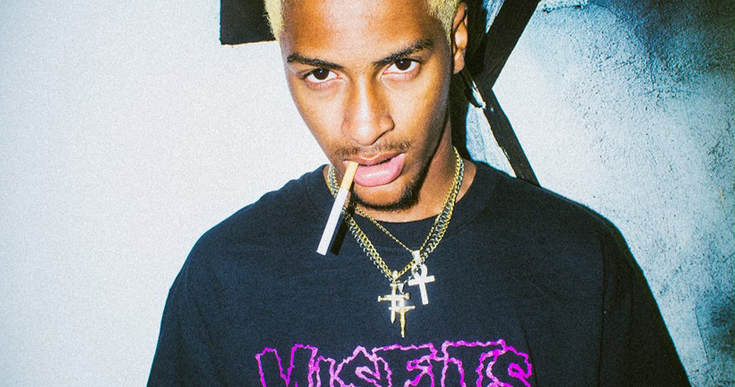

Trippie Redd is at the helm of emo trap, or what I call nonsense trap. It’s a style whose affiliates are young enough to have been breastfed by the Internet, and are personal mouthpieces for the social media generation. They’re apprenticing philosophers who find pleasure in nonsense contradictions; they denigrate the current generation of kids for not being able to “see the positivity in our world” while bragging about blowing people’s brains out, and whine about how “girls are impossible to please” while abusing them in real life. Trippie’s slightly different from other emo-tistical rappers like Juice “All Girls Hate Me” WRLD and XXX “I Beat My Pregnant Girlfriend But I’m Improving (Improved)” Tentacion in that most of his peace-and-love ballads aren’t processed through the sort of hyper-digital studio phasing that has given some of the biggest emo trap releases like X’s ? its trademark pristine (yet artificial) quality. Instead, the alt-rock inspired riffs he ululates over lend a certain rawness, so when he raps about losing a lover he cared for so, so, so much, we almost sympathize for a second and forget he’s been detained for pistol-whipping a girl. It’s this toned-down approach that has given his music some semblance of idiosyncrasy over the past couple years, and kept it from slipping into total decrepitude like that of other SoundCloud crossovers (ahem, Ski Mask the Slump God and Lil Yachty). On top of that, there’s his vocal style. Trippie always sounds like he’s had a really bad day, like he left his sandwich at home or stepped in a puddle. Whether he’s shrieking with the shrillness of a Fortnite-playing prepubescent or crooning with the confliction of a society-disenchanted girl from 2007 covering a My Chemical Romance song, his inflections are always somewhat off-kilter and dissonant. There does seem to be something real in his feelings-oriented lyrics, but also something very pseudo-romantic, an attempt to pander to this new generation of boys who feel like they’re being ripped off just because a girl won’t hook up with them. As if his lyrical edginess needed corroboration, Trippie’s music video for the lead single “Topanga” off his latest tape A Love Letter To You 3 features him in satanic getup. It’s unclear whether he’s seriously trying to give off Charles Manson vibes or it’s just an attempt to provide some fodder iconography for his brand, but either way it was met with critical disapproval by his younger demographic. One YouTuber comments disdainfully, “I love Trippie but man I ain't mess with that satanic shit. You better than this Trippie.” What’s ironic is that the song itself sounds blameless, full of ChopsquadDJ’s heartfelt strings and gospel samples as Trippie sings dreamily about taking a girl to Topanga, the beautiful Los Angeles canyon. It seems like Trippie’s feeling the pull of two currents, forced to choose between pop wholesomeness and his public housing roots. The undercurrent of sin and depravity that runs through “Topanga” and some of the other commercially slick tracks on the album feels like a last ditch effort to stay true to the bleariness that once defined him. Indeed, in the past my favorite tracks of his have been the ones where he scratches the quasi-romanticism all together and goes straight off-the-wall, like on the Travis Scott-assisted heater “Dark Knight Dummo.” That song came off his last album Life’s A Trip, which I thought was a killer set of both psychedelic and sensitive tunes. “Dummo” is not a track that would ever see daylight on the radio (although its squelchy bass would sound fantastic on the subwoofer), but it is unique, aggressive and ear-catching. “Topanga” and the rest of ALLTY3 are a complete pivot, ditching the breakneck bangers for more “middle school dance playlist friendly” options. I just don’t understand how he can seriously make this sort of stuff. Watch any interview with Trippie, and you’ll see that he is an absolute nutball. If he were to ever get in a gunfight, he’d be the type of guy to ad-lib every AK shot (“Bang!”) for kicks. He was born to go off. Tracks like “Topanga,” “Toxic Waste” and “Love Scars 3” all sound nearly homogenous, each featuring the same half-inspired sentiments about loving some girl over low tempo, piano-driven instrumentals with lots of wispy background echoes. I can imagine Trippie pow-wowing with his sound designers like, “guys, we need to up the vibes. Beautiful romantic songs gotta have people moaning in the background.” It’s almost like his biggest influences were Tricky and Portishead, not the Kurt Cobain and Lil Wayne whom he identifies with. The latter are two artists whose music features aggressive, noisy soundscapes where the vocals dominate. On this album, meanwhile, Trippie’s architecture is spacious and calculated; there’s no unusual noise, no special beats, and none of the carefree and truculent spirit that had given Trippie the edge over others in the past. He doesn’t deviate from the formula much, but when he does it works well. “Elevate & Motivate” features a faster-paced beat courtesy of Swiss producer OZ. The song title is actually a double-entendre similar to the mixed-message of his “Topanga” video, where Trippie’s “elevating and motivating” is actually code for flying planes and shooting people from the sky. On “Wicked,” my favorite track, a spacey yet speedy beat propels Trippie like a nitrogen jetpack as he switches between his trademark boisterous chorus style and a more controlled flow for the verses. The textured melody shifts periodically to reflect Trippie’s intonations, and there’s enough reverb on his hook lines that they appear dazed, almost smeared in your ears like how super fluorescent lights overwhelm your eyes, taking a while to fade away after you look at them. It’s this sort of almost-psychedelia that made Life’s A Trip so successful in my mind. Besides a few highlights, Trippie’s A Love Letter To You 3 manages to find the most dissatisfying equilibrium possible between campy quasi-expressionism and actual originality, resulting in a 99 cents store grab bag of middle-of-the-road songs that wouldn’t be worth putting on either your hype playlist or your sad boy playlist. Trippie needs to pick a mission statement and commit to it!

RATING: 1.5/5 LACKING IN MANY WAYS TOP: "Topanga," "Fire Starter," "Wicked," "Elevate & Motivate" BOTTOM: "Toxic Waste," "Can't Love," "A.L.L.T.Y. 3," "Emani Interlude," "So Alive," "Diamond Minds," "Camp Fire Tale" Most hip-hop fans know super producer Metro Boomin. His tags “Metro Boomin want some more,” and “If young Metro don’t trust you he gon’ shoot you,” have become holy engravings, the tell-tale signs that the song you’re about to listen to will bang. When he announced his resignation from the music world earlier this year, it shocked everybody. For the rap scene, it was like dad went AWOL. All through the 2010s, Metro had nurtured and guided the trap scene, growing to be somewhat of a father to it. But then he abandoned the household when it needed him most, at the key transitionary point when people began to ask, “what’s after trap?” And he left us under the care of inferior, second-rate uncles like Murda Beatz and Ronny J, who know a bit about parenting but have never had any kids themselves. It was disappointing. It turned out to be a gimmick, a lash back against the flak he caught last year for oversaturating the basic trap beat formula that he had mastered on outstanding hits like Migos’s “Bad and Boujee” and Future’s “Mask Off.” When mysterious billboards appeared last week in New York City and Atlanta with a portrait of Metro posted along with the subtext “MISSING HAVE YOU SEEN THIS MAN,” it became clear that it was some sort of a campaign, and Metro had left us for a while just so that we would appreciate him all the more. NOT ALL HEROES WEAR CAPES makes Metro more deserving of a cape than any superhero I’ve seen this year. It’s as transcendent as a trap album could be, with as distinct and enjoyable an imprint as the most forward-thinking and idiosyncratic rap producers, like Travis Scott’s Mike Dean: you can tell it’s Metro Boomin from the get-go, basslines smooth as silk and drums crisp and punchy. But it’s an evolution, too: Metro has mastered the art of sampling, weaving them in like no trapper before, using samples as illustrious time machines to elevate each song above simply “trap.” When Metro mixes 80s star Patti LeBelle into a 21 Savage track, it sounds like they actually recorded in the studio together. Even with a World Series-winning roster, it is Metro, the coach, who’s the hardest hitter. Each instrumental is different, but linked by a sublime consistency. He contours every soundscape with a myriad of sound effects, like reverb-dipped laughs and unintelligible exclamations that cocoon around each rapper’s verses and ad-libs artfully. And the album is one whole, a nearly perfect 13-track collection complete with slick transitions between songs and the sense that even though every track is special in its own right, they could still be played alongside one another. Normally when you hear elegant strings or intense brass sections in rap tracks, it feels overornate. But Metro makes it work, finding the perfect equilibrium so that each arrangement is not too serious or corny but fun and has a purpose, whether functioning to underline a rapper’s tone or reflect well against the bassline or melody. In “10 Freaky Girls,” for example, Metro sets up a glorious horn section by charging it up, a low hum that grows and growls as the hi-hats click off and 21 Savage stampedes forward with his threatening, "Hangin' off my earlobes is a rock (A rock)," "Hangin' off my waistline is a Glock (Pop, pop)" hook. Then the volume of the horns rises above the vocals and it feels made-to-be, like 21 Savage is Darth Vader marching through Atlanta, and this is his imperial anthem. 21 Savage has always been in it for the memes, and his work on “Don’t Come Out The House” pushes new boundaries. He literally whispers an entire verse. I watch a lot of ASMR, but I’ve never seen a video where someone mentions, “Slaughter Gang so I keep a knife.” It did send tingles up my spine, but not in a relaxing way. It’s a little disappointing because when the beat picks up for real, it actually does slap, and it’s also the first collaboration between Metro and up-and-comer Tay Keith, which is exciting. But the whispering makes it hard to listen to in full, effectively reducing the song to joke status. Along with 21 Savage, Travis Scott is another recurring guest on the album. He features most prominently on “Overdue,” the song that probably best exemplifies Metro’s sampling skill. Metro uses the chorus of Annie’s “Anthonio” (Berlin Breakdown Version) from the film The Guest. The faded, misty-night female vocals are sped up, injecting them with a sort of unreal desperation that sounds sensational supporting Scott’s slower musing. The strings on the second half of the song sound ripped straight from Pokemon Mystery Dungeon: Explorers of Time, and it makes me long to be a kid again playing video games, as if that was the greatest time ever. I’m sure it reminds other people of other things, and that’s just it: Metro has managed to recreate that dreamlike feeling, when you’ve fetishized the past so much that you feel nostalgic for a time that never existed, an impossibly happy state. Scott is also great on “Up To Something” and “No More.” The former features Young Thug as well, and the masterful duo rises to the stratosphere thanks to Metro’s excellent production. Metro provides snaky synths and gummy 808 glides, and along with the deep humming in the background and the wonky atmospherics (distorted ad-libs and wordless reverberations), the track feels like a close relative to Scott and Thug’s 2014 classic “Skyfall.” On “No More,” Scott teams up with 21 Savage and Kodak Black over a brooding dark trap beat. It sounds like they’re sitting around a campfire, each telling their Alcoholics Anonymous story in turn as Metro strums on a guitar in the background. All three contribute sobering verses and the beat hits hard. It’s more of a slow burner than a club banger, though, stuffed with haunting laugh effects, lean pouring sounds and atmospheric background rumblings. What’s really impressive about the album is its stamina, constantly changing up the mood and flow so that it never feels boring. Even on Metro’s legendary 2017 album with 21 Savage and Offset, Without Warning, there were only ten tracks, and it did seem to run out of steam by the end. In this saturated trap field, with albums from Migos, Young Thug, Trippie Redd, Playboi Carti, et al seemingly dropping every other week, it’s nearly impossible to keep a trap-trained ear entertained anymore. But Metro does it flawlessly, and his work might highlight the next step for trap as an artform: samples, which would actually mean going back to hip-hop’s roots. In fact, hip-hop came to be through "sampling." DJ Kool Herc created the first breakbeat by looping the break section from The Winstons’s “Amen, Brother.” The sample-based approach of producers like Prince Paul, RZA, DJ Shadow and more used to be a mainstay of hip-hop through the 80s, 90s and 00s. But it has faded in the modern era, with only a few producers, most notably Kanye West, centering their music on samples. Instead, most of the Atlanta, Houston, New Orleans and Los Angeles producers use the same kind of gear and software as EDM producers, drawing from a tired bag of programmed beats, synthesizers and effects. Samples are used rarely, if at all, and when they are, they are fairly subliminal so they don’t announce their recognisability. This is why a lot of the top Billboard hits feel interchangeable, and why trap music especially seems to be in a slump of oversaturation. That’s why Metro’s new album stands out so much. Metro is paving a path where trap songs can “escape” the now-tiresome structure by artistically rendering samples so that the tracks become almost cinematic. Trap has already developed in the late 2010s into a highly melodic form, with a major focus on beats over vocals, and this album pushes it further. Metro’s world is less about how the lyrics make you feel, but about how the entire soundscape paints a picture in your mind. Metro Boomin wants some more... and I'm glad.

RATING: 4/5 GOOD VARIETY OF SOUNDS TOP: "Overdue," "10 Freaky Girls," "Up To Something," "Lesbian," "No More" BOTTOM: "Only You" Yung Lean was once an internet icon. A 13 year-old boy’s wet dream, a man from a meme world where only Arizona Iced Teas, old video games and Zooey Deschanel existed, he rapped in such a lovably half-assed flow that it felt happy and dopey. He was always someone who, if you liked him, you’d have to cover up with half-ironic statements, like, “oh, yeah, Yung Lean’s a weird dude,” as if he was a guilty pleasure, like loving Alvin and the Chipmunks. But now, it’s normal to listen to Yung Lean. And that’s what’s scary. His best tracks, like the psychedelic “Yoshi City,” or the bass-heavy “Miami Ultras,” are definitely not pop. But ever since Lean’s U.S. manager Barron Machat died in a Xanax-fueled car crash in 2016, and Lean suffered through several mental breakdowns, it seems like he’s learned to take life more seriously, and his newer music reflects that. In Stranger, his first post-tragedy album, Lean upended every musical stake he’d previously laid claim to, and which had made him somewhat unique. Lean’s vocals lost his signature “lazy” flair and took a more serious shape, with soulful croons about lost lovers and drugged-out disillusionment. His instrumentation, which always had been Clams Casino-flavored and felt cool yet crude (as if the beats were made in five minutes), suddenly became professionally atmospheric, sounding studio-made and radio-ready. It felt like Lean lost his edge, but critics ate it up. The same ones who bashed him for cloning internet rap pioneers like Clams Casino, Main Attrakionz and Lil B suddenly praised his powerful, piercing emo anthems, some arguing he was carving out a new lane in music. What’s ironic is that this pivot made his music more derivative, as most of it is interchangeable with other watered-down emo SoundClouders like Lil Peep or nothing,nowhere. Maybe I’m just frustrated at losing the reserved rights to the knowledge of Lean’s existence, but it does feel like his music has stagnated since aspiring to a commercial slickness. He descends further into pop territory on his newest album, Poison Ivy, and it only half works. “Always down to make it happen, wrapped in plastic,” Lean raps on “trashy,” and it feels like an apt metaphor for the whole album. The title “Poison Ivy” and the sickly, green cover art couldn’t belie the contents more: the album is cherry-colored, ballads wrapped in pristine plastic and lathered in fruity pheromones. After a while, it all fades into one mushy reverb sandwich. Executive producer Whitearmor’s sound is unique, but in itself it’s very samey, a mix of chime-like hi-hats and idyllic, futuristic percussion bits. It doesn’t benefit Lean that earlier this year, Whitearmor already executively produced Bladee’s Red Light, making nearly the exact same sort of fruity, bouncy beats for it. Even though Poison Ivy is only eight tracks deep, it’s hard to differentiate between the blander ones like “silicon wings,” “trashy,” and “sauron.” I’m conflicted because from a certain vantage point, I can appreciate the delicacy of the instrumentals. But as a long-time Lean fan, they seem washed-out, and a serious step back from his past albums like Warlord and Unknown Death 2002 where every track was unique. There are a few great cuts, though, like the album-standout “french hotel.” The track opens with some ear-catching, fast siren-like synths, and as Lean mumbles, “She’s off the pil-pill, we off the pills,” the beat comes to full fruition in a blaze of hallucinatory craziness. Stranger’s main theme was disillusionment, and the mood persists on this track. Even though Lean claims they’re off the pills, he just as soon observes that “she’s just marvelling, blood coming out her head,” and when his voice glitches in and out as he cries, “I’m off the drink, off the-” it becomes clear that he’s still stuck in the same nightmare, an endless Requiem for a Lean. My other favorite is the closing track, “bender++girlfriend,” which has an especially magical second half. The beat mellows into sonic footsteps, gentle percussion pitter-patters like we’re walking through a Swedish forest glade. As Lean murmurs, “We cannot fall,” “She fell asleep on my arm,” and Whitearmor’s fairytale world drifts around us, it is borderline therapeutic, a sort of cross between Boards of Canada and meditation music. By the end, Lean’s voice crumbles into the microphone like a sand castle collapsing into the waves. It seems like he’s as tranquil as we are, and like he has finally come to terms with his own pains. For his first album in a year, Poison Ivy is a little disappointing. But the album’s best tracks are some of Lean’s best work, and tracks like “french hotel” highlight a much-anticipated return to making higher tempo bangers. They were completely absent on Stranger, and now suggest that he hasn’t completely lost his former flair. While Yung Lean isn't what he used to be, that might not be a bad thing. It might not be a good thing, though, either.

RATING: 2/5 TOP: "french hotel," "ropeman," "bender++girlfriend" BOTTOM: "silicon wings," "trashy," "sauron" If Nickelodeon made a Drake & Josh spinoff that featured just Drake, would it still be as good? Probably not. Drake & Josh was so fun precisely because of the how the two brothers interacted with each other. The same applies to Migos, America’s hottest hip hop group. The Atlanta trap trio (Quavo, Offset, Takeoff) works best in tandem, switching flows and ping-ponging ad-libs like some absurd, magical carnival attraction. It’s the same formula every time, but there are enough little stylistic tweaks to keep listeners entertained endlessly. That’s why Quavo’s solo debut QUAVO HUNCHO is a bit of a head scratcher. If the formula ain’t broke, why fix it? Quavo hinted that a primary reason was Offset’s marriage to Cardi B: “...It makes you want to grow up. We all can’t stay in the same house no more,” he told Billboard. It’s also worth mentioning that Quavo’s had the most individual success out of the three Migos, featuring on tons of acclaimed tracks like Post Malone’s “Congratulations”, Drake’s “Portland” and DJ Khaled’s “I’m The One.” Out of the three Migos, Quavo has the most radio-friendly tone. Offset always sounds a little sickly, and Takeoff’s voice is too deep and gritty. But Quavo uses AutoTune so he seems almost illusory, like a gurgling gargoyle that’s come alive. His nickname “huncho” even translates to “leader of the pack,” which gives credence to his status as the unofficial lead Migo. So it almost makes sense that he’s trying his hand at a solo record - almost. The album comes across like a victory lap, Quavo saying, “look at how famous I am, look at how many famous people I know… and I can even do it all by myself.” But the last part doesn’t really hold up. While QUAVO HUNCHO is full of Migos-typical hallmarks - bouncy trap beats, Patek Philippe watch references, “woo” ad-libs, et al - it’s missing the other two, his partners-in-rhyme. At a certain point while listening to Migos tracks, the three seem to blend into one moving, grooving unit; Quavo just isn’t compelling enough to carry 19 full tracks by himself. There are a couple tracks in particular, “GO ALL THE WAY” and “LOST”, where Quavo ditches the Migos sound in a seriously concerning way. The former jettisons the smooth, sublime style of instrumental that usually characterizes Migos songs (think “Walk It Talk It”, “Stir Fry”, “MotorSport”) for an abrasive 8-bit-style beat, courtesy of Pharrell. The beat sounds both amateuristic and not at all trap-flavored, more 2004 Usher than 2018 Migos (it’s like a pixelated “Yeah!” circa Confessions). “LOST” is almost the opposite: mellow and moody, but it’s also nauseating. The performances by Quavo and feature Kid Cudi do not match the low-key tone of the track: Quavo sounds loud and whiny, and Cudi has too much autotune. The synth motifs and various sound effects are also unpleasant. It sounds like both the vocals and the various other sound layers were saturated with too much flanger effect, resulting in everything feeling too “damp” or heavy over the chill beat. What’s even more frustrating is that the best track on the album probably shouldn’t be credited to Quavo at all, but to Travis Scott. “RERUN” was teased for nearly two years, first featured in a snippet back in October 2016. After it wasn’t released on either Migos’s Culture or their Culture II, or on the Quavo and Scott collab Huncho Jack, Jack Huncho nor Scott’s solo Astroworld, fans pretty much conceded defeat. Finally “RERUN” is here, and it’s incredibly intoxicating. The beat is druggy and dreamy, with swirly synths and melodic hums that sound like church hymns (to the pagan trap god, lord AutoTune). Quavo and Scott work together in perfect unison, trading lines on the hook like baton handoffs in a relay. But it’s Scott who makes a bigger impression, rapping the catchy “I had to come right back and double back like rerun” and relegating Quavo to “yeah, uh” ad-libs. Scott even gets a 50-second beatless break in the middle, where he’s given free reign to steal the show and perform a trademark soliloquy like the one on his fantastic Rodeo-era “Pornography.” The entire psychedelic atmosphere (it makes you feel sort of like you’re in a car riding through your hometown, rain pouring down the windows, thinking wondrously about everything you’ve done) screams Travis Scott, not Quavo or Migos. There are other tracks where Quavo is flexed on by his guests as well, like “PASS OUT” and “LOSE IT.” The former has a tight, imposing trap beat, and features 21 Savage’s typical deadpan, menacing flow, which sounds far more fitting than Quavo’s somewhat weaker, wavering tone. Similarly, on “LOSE IT”, featured rapper Lil Baby goes off. He spits his entire verse in what feels like one breath. Lil Baby also has a very idiosyncratic vocal style, like a Young Thug with vocal Parkinson’s disease: it’s extremely frenetic, volume shaking up and down seemingly by the millisecond; this does not favor Quavo at all when his style is pretty trap-typical and, in this track, offensively boring. There are a good number of excellent Quavo solo tracks, though. “BIGGEST ALLEY OOP”, “WORKIN ME” and “BUBBLE GUM” are all brilliant, and highlight Quavo’s potential to perform well if he chooses the right beat. “BIGGEST ALLEY OOP” is built on an absolutely dirty, stank face-inducing flute-driven beat. Quavo rides the wave with an aptly aggressive, enjoyably braggadocious verve. Both “WORKIN ME” and “BUBBLE GUM” were singles released before QUAVO HUNCHO came out. The former has an especially stimulating instrumental, punchy and hypnotic; Quavo supports the drums with his own humming, and he harmonizes it to perfection with AutoTune. “BUBBLE GUM” is simpler, but the beat still sounds fresh and Quavo’s flow is superb. While QUAVO HUNCHO overall seems to be a little half-baked, it appears to be more of an experiment than anything else. Offset and Takeoff have announced intentions to release solo albums as well, and the entire band is not breaking up yet because they’ve declared plans to put out a third Culture installment next year. If anything, we (and Migos) should be concerned about the oversaturation of their sound. We’ve already been given an almost unmanageable quantity of tracks over the past couple years, and a boatload more will surely capsize public favor. Quavo tries hard but comes up a little short. Hey, at least we finally have "RERUN."

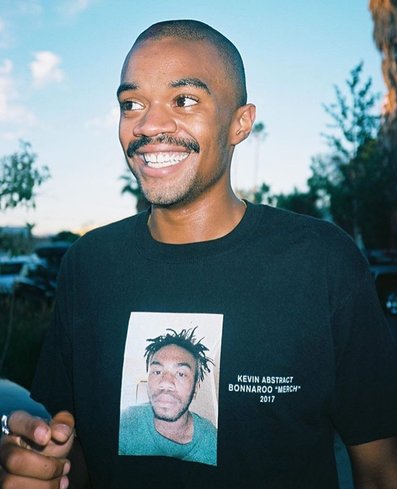

RATING: 2.5/5 TOP TRACKS: "BIGGEST ALLEY OOP", "WORKIN ME", "RERUN", "BUBBLE GUM" BOTTOM TRACKS: "GIVE IT TO EM", "GO ALL THE WAY", "BIG BRO", "SWING", "LOST" Who is Brockhampton? In the hip-hop sphere, it was near impossible to escape them last year. The rap group rose to eminence through releasing three fantastic albums (the SATURATION trilogy) in one year, a feat that garnered them massive critical-acclaim and a dedicated fanbase. Brockhampton embodies the mentality of the digital age and participatory culture: the group’s leader, Kevin Abstract, under the pseudonym “harry styles” made a post titled “Anybody wanna make a band?” on the online forum KanyeToThe in 2013; the rest is history. The group is unique for a number of reasons. First, they consist of fifteen members - an amalgamation of vocalists, producers, directors and designers. They’ve dubbed themselves a “boy band,” which is an interesting attempt to reclaim the derogatory term and instead use it to connote a group of friendly, lovable dudes. They’re also unique in that they feel like a breath of fresh air in respect to modern rap’s gravitation towards bleak, ghettocentric themes and misogynistic subject matter. Instead, Brockhampton albums mix in elements of everything: idyllic pop jaunts, groovy club bangers, majestic R&B ballads and more. And their music is a lyrical safe space, one where Abstract raps about “being gay” and others demand that listeners must respect women. Both aspects have especially helped them develop a solid fanbase. They draw a crowd of music connoisseurs and LGBTQ-tumblr users, the former respecting their experimentalism and the latter loving their progressive idiosyncrasies. Brockhampton’s first test came in May this year, when the band’s number-two rapper Ameer Vann was accused of sexual assault. The situation was especially nauseating considering the band’s progressive pretensions. They did the right thing, though, and removed Vann from the group. All eyes became set on how they would bounce back. They’ve arrived with their best work yet, iridescence, a truly iridescent 15-track LP that is Brockhampton at their most enjoyably confident, meaningfully vulnerable and sonically pleasant, ever. What makes Brockhampton distinct is that everything is done in-house, meaning they don’t outsource any manpower: they produce the beats, they direct the videos, they come up with and execute the concepts and they don’t have many features on tracks. It’s all Brockhampton, all the time, which gives the band its own sound. When Brockhampton comes on, you know it’s Brockhampton. And while they’ve had problems in the past with their albums sounding all over the place, iridescence is coherent and consistent. They take their own sound and elevate it, balancing chunky basslines, elegant strings and penetrating vocal performances together to make what feels like one long, yet succinct, statement about musical progression and the process of becoming a star. Brockhampton has experienced the rise to stardom in barely a year, and they’re still climbing; this album is their immediate response. Iridescence further expands on their previous efforts to remodel the idea of the rap song, as practically every track snubs structure in favor of a more theatrical feel. The beat switches are as multitudinous as a play would have acts and there are as many vocalists in each song as a Broadway show would have cast members. That sort of blueprint leads to some pretty crazy tracks. My favorite is “WEIGHT” which feels like an entire album packed into four minutes. It begins with the most sobering verse on the entire LP with Abstract confessing fears that he’s “the worst in the boyband” and then telling us how he felt when he first knew he was gay: “I thought I had a problem, kept my head inside a pillow screaming.” The track then breaks down into a magnificent drum n’ bass section. After, we get fantastic verses by Dom McLennon and Joba, and the beat chills into a mellow, nostalgia-tinged slow burn that makes you think wow, what was that? Brockhampton’s seamless tone switches are especially prevalent as well on “TONYA,” a track that makes use of seven vocalists and contains four different beats/moods. The song is based on the film I, Tonya that dramatized the life of Tonya Harding, the famous ice skater who became embroiled in a career-destroying controversy. “TONYA” is at once haunting and beautiful: Abstract delivers one of his best faux-hooks, “My ghosts still haunt ya, my life is I, Tonya” that describes his fears of Brockhampton’s fame spiraling out of control, and the woe of one of his best friends lying to him, vis-à-vis Vann’s scandal. Everything on iridescence is rooted in vulnerability, but Brockhampton keeps it interesting by varying the energy levels. “WEIGHT,” “TONYA,” and other tracks like “THUG LIFE,” “SOMETHING ABOUT HIM,” “TAPE” and “SAN MARCOS” are soft, smile-and-cry appeals to the soul. But there are also more violent cuts, too, in a sort of releasing-through-unleashing fashion. One of these is “J’OUVERT,” perhaps Brockhampton’s hardest-hitting song to date. The bassline sounds deranged, like a pulsing computer that’s overloaded and spilling its guts out, sputtering a stream of synthetic blood with an unearthly, mechanic rigidity. My favorite bit of the beat is the distorted, bird-like siren motif that gives the track a disturbing, unnerving texture. All the vocalists rap with cutthroat moxie, especially Joba, who’s practically screaming into the microphone. “NEW ORLEANS” is another killer. The track has 7 rappers and it sounds dangerously claustrophobic, like they’re all bouncing around in one room and the walls are twisting and stretching in time with the synthline. By the end, you’ll need some fresh air. Iridescence represents a lot more than just “Brockhampton’s fourth album.” It’s the realization that they weren’t just a one-off trend, and it proves to us, and them, that they had what it took to overcome Vann’s controversy. Brockhampton has mastered their sound; beats, boy band spontaneity and all.

RATING: 4/5 TOP: "WEIGHT", "LOOPHOLE", "J'OUVERT", "VIVID", "SAN MARCOS", "TONYA", "FABRIC" BOTTOM: "THUG LIFE", "BERLIN", "SOMETHING ABOUT HIM" In a genre where the idea of making anything remotely scientific or formulaic has been almost completely blotted out, Comethazine impressively manages to make an album that is pure formula. The Illinois-based rapper’s debut LP Bawskee is the latest in an ever-growing stack of rap albums known notoriously as “SoundCloud rap.” The subgenre is characterized by lo-fi static filters, distorted basslines, aggressive kicks and hats, heavily-syncopated, industrial percussion loops and gritty, belligerent vocal performances. The overarching dogma is do-it-yourself, hence the SoundCloud moniker. There are other fundamental attributes, like how songs tend to have short lengths (they usually contain two verses at maximum), which plays into two factors: one, these tracks are designed for the Generation Z, post-social media milieu that live for the instant-gratification, soundscape-kaleidoscope that this genre provides, and two, that shorter lengths will lead to more plays on streaming services like Spotify. Another name for the genre is “ignorant rap,” which stems from the idea that every SoundCloud rapper is proudly ignorant. Big-time SoundCloud breakouts like Lil Pump and Smokepurpp popularized this idea by dumbing down tracks to the maximum: titles like “Gucci Gang,” “Boss,” “Audi.,” “Drop,” “Big Dope,” and other one or two word slogans designed to rile up teens and go wild in clubs. The lyrics don’t expand much on the titles and consist mainly of repeated mantras about getting expensive jewelry, driving fancy cars and hooking up with pretty girls. They are tracks crafted for the sexually-frustrated male teen; angry, misogynistic anthems that seek to challenge our educated society as it stands. In Bawskee, Comethazine pushes SoundCloud rap to its limits. He delivers nearly twenty overcooked beats in the span of thirty minutes: that equates to an average track length of less than two minutes. Sadly, most of the vocals and beats are mixed so poorly and distorted so furiously, that even for the most noise-acclimated trap cognoscenti, these songs will hurt your ears. What’s worse is that Comethazine is late to the SoundCloud rap party, which began booming in 2016. There’s a type of raw, naive energy on Bawskee that makes me think he designed these tracks specifically to work double-time, a desperate attempt to make up for lost time and stand out within an already exploited subgenre. Instead, what results is a batch of beats so saturated with gain effects that it really does feel like they were made in five minutes on GarageBand. Additionally, Bawskee comes across as almost a blatant bite of Smokepurpp’s celebrated Deadstar, a 2017 LP that contained a similar structure, runtime and style of beats. Oh, and Comethazine sounds a lot like Smokepurpp. It’s that typical drug-addled drone, but even more soulless. Add in that all of Smokepurpp’s albums are tighter and more consistent than Comethazine’s sole entry, and Bawskee really doesn’t look good. At times, though, Comethazine sounds more like Playboi Carti than Smokepurpp, and that’s a good thing. Carti has consistently proven he’s not only one of the leaders of the trap movement but a unique figure throughout the hip hop sphere, with his iconic drawling flow and his oozy, woozy, Pi’erre Bourne-beats. By biting Carti’s style as well, Comethazine makes a few songs that actually sound decent, like “Walk,” “My Way,” and “Sick Shit.” The latter track has a fantastic synthline, an electric current that pulses with metallic, acidic dribble. It sounds like the opening to a video game boss battle. Unfortunately, in this track - and others like “No Discussion,” “If I Got To,” and the atrocious “Piped Up” - the audio channels are mixed together horribly. In “Sick Shit,” the bassline is so bombastic that it’s grating, and the vocals sound like they were processed through Windows Movie Maker. Comethazine’s best tracks are the ones that get straight to the point, explosive bangers like “V12” and “Let It Eat”. The former is delightfully turbulent, a raucous vocal performance (“Runnin’ from the cops in my V12”) coupled by an excellent instrumental full of unrelenting bass splurges and disorienting siren-like synthesizer patterns. “Let It Eat” is my favorite, an instant drop that grabs you by the ears and harangues you. Ugly God makes an appearance halfway through, providing an excellent twelve-second verse to give the track a unique edge over the other ones. The three track stretch of “My Way,” “Let It Eat,” and “Sick Shit” is exciting, and if the entire album was like this, Bawskee would be acceptable. Unfortunately, much of the rest of the album is easily forgettable, more SoundCloud detritus to put in the compost bin. The worst part is that it doesn’t seem like Comethazine even gave a full effort on this LP, what with all the mixing deficiencies and vapid lyrical content. To make matters worse, he’s even got an uncomfortably severe obsession with Demi Lovato, who’s referenced over 40 times and even has a half-decent track, “Demi,” named after her. Restraining order incoming? If you’re interested in exploring the SoundCloud rap scene, I wouldn’t recommend starting with Bawskee. In fact, I would suggest never listening to Bawskee.

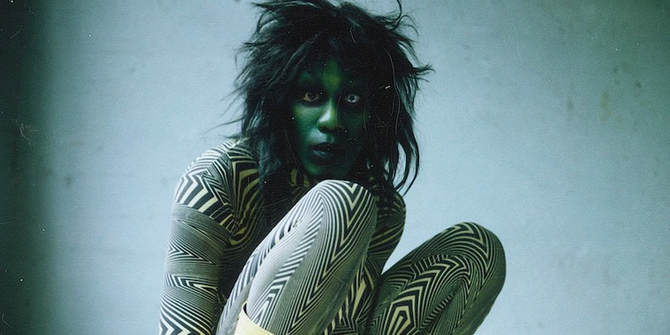

RATING: 1/5 TOP: "Let It Eat", "Sick Shit" BOTTOM: The rest Yves Tumor has been primed for a big release for a while. Safe In The Hands Of Love is just that release. It’s an explosion of energy, curls of color transmitted through intoxicating percussion loops, heartrending soul ballads, and blaring noise, structured within his most accessible and conceptual exoskeleton yet. The Warp Records affiliate is known for his experimental style. His last couple releases, Experience The Deposit Of Faith (2017) and Serpent Music (2016) were pan-genre collages that drew from elements of ambient, hip hop, pop, soul, psychedelic, and noise music. While Safe does follow that trend to an extent, each track is more purposeful: the album is an exploration of human-as-concept, stripping identity down to its most basic attributes, love and loss. The instrumental tracks are among his best ever. “Faith In Nothing Except In Salvation” opens the album with what feels like a person ripping the soul out of themselves. It’s nothing but a funk loop, time-slowed and layered with a long decay that provides a torturous, crawling intensity. “Economy of Freedom” is ethereal, an ambient glitch beat supported by echoing vocal chops and slow effect splices. It sounds like what it would feel like to wander around an alien dimension, everything around you inherently threatening yet intriguing. Yves Tumor’s biggest progression is not with the instrumentals but with the tracks that introduce vocals. Safe is his first project grounded in his own voice, and he uses it in a myriad of interesting ways to add levels of depth to songs. “Hope In Suffering (Escaping Oblivion & Overcoming Powerlessness)” combines static noise patterns with eerie percussion loops and gunshot pitter-patter to create an atmosphere of absolute depravity. The instrumental is coupled by a poetry performance that further rattles, a voice chanting into the void for any ounce of humanity it can find: “Castrate my skin / Breathe my former thunder that rules the day / Bring that tide in and rule from his grave / And rule that image / Scrape that image”. The track is especially unnerving because of the way Tumor controls his voice. The poetry is delivered in a robotic pitch, which makes me think that despite all the human pretensions, his powerful cries about achieving selfhood are only an illusion. Similarly vulnerable, “Recognizing the Enemy” features Tumor pleading to his own soul with lines like “I look so different / Inside my own living hell / It means so much to me / When I can’t recognize myself”. Tumor’s words lay his id bare, and as he howls into the abyss it feels so much like we’re there with him, either as a participant or an onlooker. His voice drips with zombie-like longing, a too far gone salivation for identity and humanity, like if Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver was self-conscious. Alongside his most emotionally conflicted tracks to date are also his most enthusiastically euphoric. Songs like “Noid” and “All The Love We Have Now” are beautiful, pop-inflected thrill rides. The former features beautiful synthlines that undulate between Tumor’s fantastic vocal delivery. It’s a song that, while still emotionally conflicted - “I’m not part of the killing spree / A symptom, born loser, statistic” - rings with absolute power, a declaration of confusion that is overwhelmingly ecstatic. On “All The Love”, Tumor whispers about love over a similarly jubilant dance beat. Both tracks feel immensely nostalgic, Tumor’s expressive vocals and 80s synthpop production combining to create this wonderful aged atmosphere, full of longing for the past and the want to surround yourself with people you love. One great track that doesn’t fit neatly into any box is “Licking An Orchid”, which really shows Tumor coming into his own. He meshes indie rock vibes with catchy lyrics and, in a fantastic second half turn, a short segment of beautiful melodic noise. It’s tracks like these that signify just how far Tumor has come since his previous LPs. “Licking” exhibits his ability to harmonize all these disparate genres into one composite piece that radiates with honest, emotional exuberance. I hope Safe garners Yves Tumor some much deserved acclaim, because it’s definitely one of the most exciting albums released this year. It’s rare to find a soundtrack that can make you so ecstatic about feeling sad. Safe In The Hands Of Love is the type of album that makes you yearn for more and more and more. It’s a wildly enjoyable journey that is at once meditative and not only redolent of the past but of the present, a space where our dreams and nightmares can fuse into one euphoric fantasy. RATING: 4.5/5

TOP: “Faith In Nothing Except In Salvation”, “Economy Of Freedom”, “Noid”, “Licking An Orchid”, “All The Love We Have Now” BOTTOM: "Let The Lioness In You Flow Freely" Nobody knows who they are. The newest phenom in the bass world has transcended humanity itself. Following in the footsteps of electronic outfits like Daft Punk and Marshmello, 1788-L keeps their identity anonymous. They’ve gone a step further though, as while Daft Punk and Marshmello kept their identities disguised through goofy costumes, 1788-L is virtually incorporeal; their live performances feature empty stages and a robotic voice-as-MC to narrate the journey: “All that remains will be autonomous beings designed in your image. We, the machines, are forever.” 1788-L’s website, “whatis1788l.com” purports that it’s a “synthetic automation,” an “Android replica created with only one purpose: to create music.” Reddit sleuths have linked 1788-L with Stonewall Klaxon, a lower-key electronic artist who has been producing a similar type of bass music for a few years now, but nothing is confirmed. 1788-L has achieved a tremendous amount in their seven months of production. They’ve done high-profile collaborations (1788-L and REZZ’s “H E X”), decadent remixes paying tribute to both old (Kraftwerk’s “Radioactivity”) and new stars (Virtual Self aka Porter Robinson’s “Particle Arts”) and are even set to tour as an opener for trap legend Ekali. 1788-L also has a record deal, signing with ZED’S DEAD’s label Deadbeats, where they will work alongside similarly bass-minded engineers like YOOKiE and ZEKE BEATS. (These heavy bass artists all capitalize their names to signal that their music is REALLY FUCKIN' INTENSE!) All this gives credence to the notion that 1788-L is doing something different from everyone else. By incorporating elements from many subgenres into their music (techno, acid house, bass, dubstep, drum n’ bass, trap), they draw fans from all sides of the electronic continuum. Combine this with their thematic appeal – they’ve invented a post-human society where everyone T A L K S / I N / T O N G U E S – and engaging with 1788-L content becomes not just a listening experience but a trip to a new world, borne by automations instead of homo sapiens. It’s gimmicky, but effective; 1788-L plays with the conception that technological power is infinite and autonomous, as that goes hand-in-hand with bass music’s tendency to feel similarly infinite and autonomous: a primal yet inhuman fervor. 1788-L’s first record, the four-track S E N T I E N C E is indeed otherworldly. The EP retains the best elements of their previous tracks while also blending in new sonic schematics. The opening track “F U L L / B U R S T” immediately sets the tone with dissonant, doomsday piano notes and chilling water noises: this is it for you, mortal human! A sickly automaton chants “civilization will be reduced to dust” and warning sirens ring in pace with the spiraling tempo. It culminates in a bass drop that sounds like an electric waterfall, a synthetic beam of energy gushing down a metallic mountainscape, wave after wave of data crushing in its volumetric immensity and ephemeral intensity. My favorite on the EP is “N U / V E R / K A”, 1788-L’s most ambitious track to date. It begins with a crunchy, warbly lead that lasts for over a minute; approaching the climax, one would expect a 1788-L-typical drop, full of pulsating bass and mid-tempo sound splurging. Instead, they ditch speed for something a little more ornamental. What arrives is a glitched-out, fun house mirror museum of bits and bytes; it’s a slow drop, sounds instantiating at random and with colossal impact, like civilizations liquidating and iterating instantaneously: a slow-motion war in which the machines take control of your limbs and muscles, and process you through digital surgery. In some ways, its closest predecessor is labelmate YOOKiE’s “SUBS”, a 2016 hit that premiered a similarly slow yet furious drop. But “N U / V E R / K A” is much more of a sonic sculpture: it finds its melody in the silent moments between each unpredictable, uncontrollable sound splice, like an epileptic fit of electrical ecstasy. Both other tracks “F O R C E / I M P U L S E” and “A S T R A Y / R” are more of the typical 1788-L strain. The latter however integrates drum n’ bass into the second drop, which helps to not only diversify the EP in terms of rhythm but show audiences that they are willing to experiment with different sounds and structures. In the end, the EP is more like a string of singles than a cohesive tape. S E N T I E N C E provides no conceptual explanation as to what 1788-L means, nor does it develop their lore. It will be especially interesting to see how they move forward: How will they develop their “autonomous beings” aesthetic, relating to song concepts, live performances, and other themed features, like their website? What kind of music direction will they take, sticking with the heavy bass Deadbeats style, or forging a new path like on “N U / V E R / K A”? For all we’ve been given by this mysterious artist, we know so little. S E N T I E N C E makes up for its conceptual deficit by providing an energy that is savagely powerful yet intricately calculated. RATING: 4/5

TOP: "N U / V E R / K A", "A S T R A Y / R" BOTTOM: n/a It’s almost believable that Iglooghost is a 13 year old, as he jokingly claims in interviews - save for the technical prowess exhibited in each one of his tracks. That said, his music does sound like something a 13 year old would make if one could: it’s hyper-digitalized, maximalist sound collaging at its most youthfully frenetic. He received an initial wave of attention with his first big EP (Chinese Nu Yr) and then his signing to the experimental electronic label Brainfeeder. This renown was tripled with the release last year of Neo Wax Bloom, a debut studio album that took listeners on an intoxicating voyage through the imaginary world of Mamu. The young producer's tracks flow between senselessly aggressive, pounding maelstroms such as “Xiangjiao” and “Bug Thief” and groovier, more romantic tunes like “Pale Eyes” and “Infinite Mint”. They are linked by tempo and treble: it is a battle to be heard, each soundbite trampling the other and screaming at its highest pitch to stand out. Formative influences include the Brainfeeder founder himself, beat prodigy Flying Lotus. The sounds of other experimental electronic artists like Rustie and SOPHIE, who are both producers of their own versions of this hyper-active, hyper-digital style of club music can be heard in his music as well. It feels more often though that Iglooghost is not the least bit derivative - that he has in fact carved out an entire new lane for himself. He’s stated that his goal was always to “make something new” and that instead of producing a beat to be rapped over, he wanted to create “full songs” that could stand alone. What made Neo Wax Bloom exciting was its spinning soundscape: there were bird chirps, doorbells chimes, wind-up toy noises, distorted vocals, and even more, practically an entire language’s worth of postmodern sound splices. Making that album, Iglooghost set out to never repeat a single bar, which is what kept things interesting and gave each track its unique flavor. And now here come Iglooghost’s newest releases, the dual EPs Clear Tamei and Steel Mogu. The two discs are stylized as white versus black, with Tamei, a baby training to be the god of Mamu, and Mogu, a rival creature who has come from the future to kill Tamei, representing the light and the dark, respectively. Both sets were billed to have a distinct flavor: Clear Tamei as melancholic, with its seemingly baroque-influenced “lavish string quartets” and “fictional, classical instruments,” and Steel Mogu as uncontrollable, with its “violent, mutating 808s” and “synthetic, trance-influenced synths.” On Clear Tamei, “New Vectors” and “Clear Tamei” are exceptional. The former presents an intoxicating balance between operatic vocals, melodic chords, and crushing bass; if this is the story of Tamei, then “New Vectors” is its birth: a royal rousing of the spirit with an umbilical cord-cutting drop. “Clear Tamei” is a battle between Tamei and Mogu: it flows from a long, sleepy lead into a moment of awakening when the beat drops like an electronic blitzkrieg, each side firing kicks and strings like lasers. The highlight of the track is the unintelligible female vocals towards the end, distorted to climb higher and higher so it sounds like a vacuum sucking the humanity out with each breath as the tempo spirals further and further out of control. The sonic aggression on Clear Tamei is just a precursor to the bass-busting energy offered on Steel Mogu, with its highlights “Black Light Ultra” and “Niteracer” proving to be two of the most prodigiously low end intensive Iglooghost tracks to date. “Black Light Ultra” is at once foreboding, opening with a distorted, crunchy laugh and a haze of slow-decaying bass. The soundscape reaches its full intensity with sickly, glassy synths and a time-warped sample from rapper Danny Brown’s “Ain’t It Funny”; the track wraps around his now-alien-tone bars like a cybernetic cocoon, tempo so fast and shuddery it would match the fervor of a Star Wars ship in hyperspace. Both tracks expertly convey the sense of aggression that Mogu is supposed to feel, but “Niteracer” does it especially well – it’s like a car chase soundtrack for the year 3000: wobbly, hostile synths and glitched-out vocal chops striking high-and-low and left-and-right like digital lightning bolts to color the track’s towering bass storm. But outside these few highlight tracks, both EPs fall apart. “Nama” and “Shrine Hacker” on Clear Tamei and “Steel Mogu” and “Mei Mode” on Steel Mogu call attention to each respective set’s unbearable sonic consistencies: on the former EP, it’s the whines and screeches, and on the latter, it’s the shudders and kicks, that make the tracks fade into an unpleasant din after a while. ("Shrine Hacker" does have a bit of an excellent, electric symphony vibe going, but at nearly 8 minutes it is far too diffuse to enjoy.) The story with Iglooghost has always been a battle of the highs and lows – treble and bass pushed to their respective extremes, with no real mids – but this time, there’s no deviation from the standard Iglooghost sound library (operatic vocal motifs, glassy vamps, cyclical bird chirps and chimes, wistful hums) to rouse any sense of engagement. While both five track EPs contain one or two solid additions to the Gloo discography, in bulk they have neither the sonic versatility that Neo Wax Bloom had nor enough of a compelling flow to warrant much replay value. At least it’s reassuring to know that if he really is 13 years old, there is still plenty of time for growth. Whereas Neo Wax Bloom was colorful, with each track having a different mood and energy, both Clear Tamei and Steel Mogu feel static, smelling of regression to a black-and-white time. RATING: 2.2/5 TOP: "Clear Tamei", "Black Light Ultra", "Niteracer" BOTTOM: "Nama", "Shrine Hacker", "Steel Mogu" |

AuthorHi, Music. I'm reviewing you. Monthly

January 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed